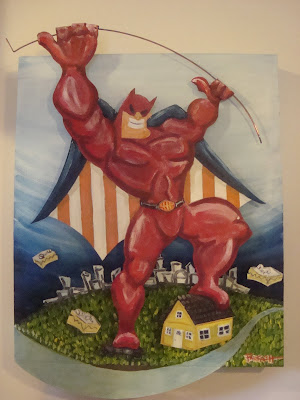

Post by the Hawthorne Hawkman. First image from www.progressillinois.com, second image from www.comunidadsegura.com.

Post by the Hawthorne Hawkman. First image from www.progressillinois.com, second image from www.comunidadsegura.com.After I reviewed a 2007 Illinois legislative audit of CeaseFire, I introduced this blog and

that post on the

Minneapolis Issues Forum. CM Gordon quickly responded with several links that explained his support of the program, and I promised to actually READ what he sent me. Hey, somebody's gotta do it.

Gordon's first link was just a few paragraphs from a foundation that gave CeaseFire money, and wanted to brag about how effective their money was. Due to the brevity and subjective nature of that link, I immediately disregarded its content. The third link went to a 400-page report, and who has time to read 400 pages of dry research findings on a volunteer basis?

The middle link brought me to a

still-arduous 229-page report, and I've decided to slog through that. I'll post what I find interesting here on NXNS. For now, I've made it halfway through the report. I haven't had time to really digest it, so like a momma hawk feeding her young, I'm just regurgitating certain points here. My commentary will come once I've made it through the report in its entirety, but readers are of course encouraged to weigh in.

Here's what the Northwestern University report has to say. First, a story from one participant in the program:

"The [Black Peace} Stones are based on the South Side, whereas the Fours [four Corner Hustlers] and Vice Lords are based on the North Side. Last year, the Stones tried to 'cross the street' to sell drugs. The conflict, then, was about territory between 'pack workers' [men selling on corners]. So far, [the area] has been “fortunate.” They have not had any retaliations. One reason K____ and D_____ have been so successful in keeping conflicts down is that “they all work together. They all sell the same sized bags for the same amount of money. They got nickle [$5 bags], mid-grade, saw bucks [$10 bags].”

"An important program strategy was to organize rapid community responses to shootings. Following an incident, outreach workers and other staff members were to conduct a door-to-door canvass in the vicinity of the event, distributing program literature and spreading word that a collective response by the community was being organized."

"The message was always short. 'Stop the killing,' or 'No more shooting.' An advertising firm working pro bono with CeaseFire developed at 'Stop Killing People' campaign and associated signs and bumper stickers. CeasFire managers frequently drew parallels between their efforts and campaigns to stop smoking and promote seat belt use, where the messages included 'smoking kills,' and 'click it or ticket.' They cited public health research indicating the volume of literature distributed is paramount in changing the way people think rather than the details of the message. A senior program manager argued, 'It's not so important how perfect the message is but he intensity of the messaging. The goal is massive messaging.'"

"Potential clients were approached on the street by outreach workers, who were constantly in search of suitable, high-risk young men to meet their caseload quota. Many likely-looking prospects refused to become involved at the outset, while others dropped out quickly. We had little prospect of knowing whom any of them were. In order to reassure their clients – and protect their records from subpoenas – outreach workers identified their clients in their records, and to their immediate supervisors, only by code numbers and nicknames. So closely held was information about clients that, if an outreach worker left the program, by-and-large his clients were lost as well. This also meant that we did not have access to the information required to track clients’ arrest history using official records."

Many CeaseFire branches operated out of already-existing social service delivery centers and non-profits. This led to conflicts between the CeaseFire mission and the goals of the preexisting non-profit, including having CeaseFire employees writing grant proposals under the direction of the host Executive Directors.

And here's how one target area was described: "Today many sections are dotted with vacant lots where abandoned buildings that were beyond redemption or scarred by arson were demolished. The strength of the area’s rental housing was undermined by the deferred maintenance practices of absentee landlords, and more recently the area has been targeted by predatory mortgage lending companies."

"In another area, the issue was not so easily resolved. The host agency had developed an oppositional stance toward both the mayor of Chicago and the superintendent of police. Years before, the host had organized a protest demonstration at the mayor’s family’s home, as part of a residential picketing initiative, and they had attempted to embarrass the police superintendent at a press conference. These incidents were not well received. When the organization was selected to be a host agency for CeaseFire, objections were raised by both parties.

"Indeed, the host agency’s sentiments had not changed much, and some of its staff members continued to have issues with the police. This led to very poor communication between them, and eventually to conflict and name-calling. In the end, many CeaseFire employees were let go, and the police commander in the area made a point to work with the new staff hired by a replacement host organization."

While giving job opportunities to ex-felons is commendable, many had no prior experience with employment of this nature in regards to accountability and record-keeping. Also, keeping clients' names confidential added an extra layer of difficulty in tracking results.

"...their voice was fragmented and often contradictory, leaving the sites to piece together a program as they could...The instability of CeaseFire funding, the demands of the job, the high-risk backgrounds of most violence interrupters and outreach workers, and drug testing contributed to staff turnover. And, this came with a cost, most visibly in outreach worker-client relationships that could not be easily rebuilt

with another staff member."

Funding inconsistencies and a lack of job benefits contributed to staff turnover as well. For some reason, contracts stipulated that workers could work 900 hours (just under six months) and then take 30 days off. This also disrupted the relationship between outreach workers and clients. So many outreach workers had overlapping jobs, including one who "was in real estate, specifically the foreclosure business, and he had mediated between people whose homes he had tried to buy."

Sound familiar?

The majestic dysfunction of Chicago politics didn't seem to help CeaseFire much either:

"To further complicate matters, a day after this budget announcement was made, the state released the findings of an audit of CeaseFire’s activities. The audit provided its own evaluative measures, and argued that the program had no impact on crime. According to the audit, CeaseFire had not been able to demonstrate its effectiveness in any significant way. Most of the remaining criticisms in the document focused on run-of-the-mill accounting errors that easily could have been made while trying to manage more than 20 active sites.

"The audit had been initiated by longtime critic of CeaseFire, a powerful state senator representing the city’s South Side and a prominent leader of the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus. One particular complaint of the Caucus was that CeaseFire was directed by a white epidemiologist. It did not matter that the CPVP staff was primarily Latino and African-American, and that the sites were located in almost completely Latino and African American neighborhoods. Their opposition explained why CeaseFire was a project of individual members of the state House of Representatives, and was never able to secure a permanent budget line debated by both houses of the General Assembly. Many observers wondered whether the audit was unbiased, and certainly the exquisite timing of its release was quite damaging to CeaseFire: the media focused as much on the audit as the budget cut."

So what did these outreach workers do? One illustrated his tasks this way: "I help them get ID cards and driver’s licenses. I’ll take them to their first driver’s test. If they don’t have a car, I even let them use mine. If a guy is living with his friends, he’s probably sleeping on a couch or on the floor. He’s not gonna be doing nothing. I’ll take [clients] down to Fullerton, where all the factories are, and fill out like 100 applications, like a mad man. I call that behavior modification."

Outreach workers reported that 81% of their clients claimed to have "never held a job." This doesn't QUITE line up with evidence showing that 50% of clients were employed full- or part-time at the time of service. These clients had to meet four of the seven following criteria: gang involvement, key role in a gang, prior criminal history, involved in high-risk street activity (i.e. drug markets), recent victim of a shooting, between the ages of 16 and 25, recently released from prison.

90% of clients reported being involved in a gang.

"Almost everyone (89 to 99 percent) who reported the listed problems indicated that CeaseFire was able to help them. Overall, clients reported an average of 2.6 problems, and receiving help for an average of 2.3 problems. In total, clients obtained assistance for 88 percent of the problems they reported facing."

"Jobs were the number one concern of CeaseFire clients, and many reported receiving assistance in finding one. However, this does not mean that they were hugely successful in actually securing a position. At the time of the interview, 25 percent of clients were working full-time; another 25 percent were working part-time, 38 percent were looking for work, and 12 percent indicated they were unemployed. The employment gap between job seekers who received assistance and those who did not was still considerable, however.

"Among clients who recalled receiving assistance, 52 percent later were working full or part time, and 48 percent were unemployed and looking for work. In contrast, among those who did not receive assistance, full or part-time employment stood at only 32 percent, and 68 percent were out of work. These differences were mirrored in their satisfaction. Among those who received assistance, 58 percent were 'very satisfied' with their job situation, and another 31 percent were 'somewhat satisfied.' In contrast, those who did not receive assistance were 'not satisfied' 43 percent of the time, and only 36 percent were very satisfied. One satisfied client tells us, 'Last summer I was selling dummy bags out there, I was bogus. I joined CeaseFire to get a job. CeaseFire hooked me up with it [the job].'

And that does it for part 1 of this report. Hopefully readers are still awake enough to offer their reactions.